It is, of course, right that philosophers should speak as believing Christians. It is right that they should do their philosophising in a conscious openness to theology… But it is not good that they should confuse the philosophical task of understanding the world as it presents itself with elements randomly introduced from Christian proclamation. The result of that will be a deformation both of theology and philosophy. Theology needs the philosopher’s reflection on the moral sense of the world, in order to think seriously about the fulfilment of creation. For without the love of what is, the “new creation” is an empty symbol – or is it a clanging cymbal? New creation is creation renewed, a restoration and enhancement, not an abolition. Not everything that can be thought of as future can be thought of as the Kingdom of God. A brave new world of cyborgs is not a Kingdom of God. God has announced his kingdom in a Second Adam, and “Adam” means “Human”.

One thing that is at risk in this approach, as in a thousand less articulate and less measured approaches along the same path, is the disappearance of scientific knowledge from the criteria of moral responsibility. We are invited to set the observation of nature aside, to cast ourselves on novelty. It is, indeed, striking how scientific curiosity – inadequate, one-sided and inconclusive as much of it may have been – has come to be banished from the discussion of homosexuality. Adams has done us the service of displaying the intellectual underpinnings of this development: a concept of value that has parted company with a concept of reality, a division between the good and the real. But moral responsibility to the real is precisely what the dialectic of creation and redemption in Christian theology safeguarded.

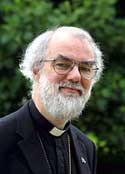

Oliver O’Donovan Creation, Redemption and Nature