“Rocket fuel”

Many witnesses

The spiritual sons of Abraham are the ones who can tell the story of Abraham. Their narration of the action of God is witness to their paternity. God, the first actor of Scripture, creates a community, composed of patriarchs, prophets and saints, into which are to be integrated. He makes this cloud of witnesses and this diversity of speech and action shape us. God creates these many words and voices, and this crowd, for us. This crowd surrounds and accompanies us, and gives us our place. The witnesses of the old and new testaments form a single chorus that cheers, and shouts warning and encouragement. They line the road on which we now travel after the Son, willing us on, lifting us with their breath, and driving us along after him. They urge us not to give ourselves away to those other lords who prey on us, and they tell us to pass their encouragement and warning on. They are conveyors and amplifiers of prayers, who make the requests we do not yet know how to make for ourselves. The Holy Spirit utters these patriarchs, prophets and saints, and bears their voices to us. In turn they bear and utter the Son, and are made holy in the process. But these many witnesses are not replaced by the Son. The new testament does not replace or displace the old testament. These many witnesses, the old testament as much as the new, now mediate Christ to us. As he mediates them, they mediate him, and all their mediation is his work.

D'Costa on the university

I have found a new hero – he is Gavin D’Costa. I heard him give an impressive paper last summer on the origins of the university in the medieval Catholic Church. He introduced it by saying that after twenty years of teaching theology in Religious Studies departments he has just come out – as a Christian. This was moderately amusing (and this is the best I can do for an emotional response to D’Costa’s revelation). D’Costa’s paper was the last thing I ever attended at the systematic theology seminar of King’s College London – it might have been an epitaph on what had been until two years previously the last place in England in which Christian theology could be studied.

But now, on the day I was in Edinburgh to make the case for Christian theology for the university’s sake (see postings in ‘Theology and the University’) I found D’Costa’s Theology in the Public Square: Church, Academy and Nation. It is a joy. Here is a blast from the last page:

Education is central to the development of civilization and if the Church fails to transform education at every level, then the future of the Church and the world are in the deep trouble. If the North American and English public cannot see this, then they should drop all the rhetoric about fostering genuine pluralism and admit the ideological nature of their secularism. This would involve suppressing history – as the recent contested European constitution exemplifies, where the Christian heritage of Europe is passed over in silence. It is up to the churches in North America and English to take up this challenge, to bring the light of God to shine through the portals of the university, to allow for a revitalization of Christian culture so that God may be given glory and the common good thereby served.

This book says what seemed to have become unsayable, in fact it blurts it out.

Scripture and the Christian community

Scripture is the learner’s articulation of the lesson she receives from her instructor. This lesson can only be read in partnership with Israel, by the baptised community given the Spirit by the obedient Son. Thus the Christian can learn only within the Christian community, and only as this community itself learns from Israel, properly recapitulated by the Son. The Son transforms our movements into those of the community re-figured by him. Scripture is the orthopaedic tool by which a new set of practices are taught. It is the set of protocols which learners must learn to internalise, so the Word of God becomes their own mind and word. The single intention of the law is to propel its students towards adulthood and to the stature of Jesus Christ. The process of the production of the holy people is not finished. The discernment of progress, and thus the exercise of judgement, is part of the process of refinement. But if the law itself has become disordered, or Scripture is no longer properly heard, it can no longer order people into the place right for each. The Law without the Spirit effects only to stall our growth. Then the law, good and necessary to us in each specific stage, would confine us within it, just when we should be released and encouraged forwards to the next stage. The law designed to build us up, itself needs be maintained, and Christian doctrine kept in good order, so it performs this purpose of building up a people. The law is effective as long as Christ is present to his community by the Spirit.

Hermeneutics is the discipline the moderns had to invent after they had rejected ecclesiology. The Christian community is the proper reader of Scripture, and Scripture builds that community. Scripture and the Church are mutually constituting. The Church, the Body of Christ, is the only hermeneutic of Scripture you’ll ever need.

Witness

Surely it cannot be all that difficult to understand what Norman Kember is about. The man is a witness. ‘Witness’ is a Christian technical term of very long standing (Greek: martyr). The witness simply goes, watches and speaks out about what he sees. He is a witness when he observes the brutal grind of life in much of the world, for example, at the Israeli checkpoints that blight life in the West Bank, and then comes home after a couple of months to tell us about them. He is a witness when in Iraq he hears about people’s experiences, and is seized and held hostage, and afterwards is able to come home to tell us about it. And he is a witness when he is seized and put to death, as one of Kember’s colleagues was.

The witness just takes the knocks he is given. He witnesses to his master’s victory by not being frightened of violence and death, or of the incomprehension and derision of the on-looking media.

In terms of family and of his own career as a doctor Norman Kember had made his contribution already. In the UK, if you are over seventy years of age it is thought that you can have nothing more to contribute, and can only hope not to become a burden. But a man with grandchildren might well decide that is something that he can do for his grandchildren’s generation. He can point towards an alternative form of politics, of truth and peace, by witnessing the violence in Iraq. At the same time Kember’s was also an act of witness against the our attitudes towards older people.

Obviously the media do not understand how there could ever be anything worth dying for. But I think we owe it them to explain, and we could do this in terms of peace, truth and justice. Or, to baffle them completely, let us tell them that Christ compels us.

Alan Brown

There can be no ghetto mentality within Orthodox theology. Theology which contents itself with speaking to a closed group, or which happily ignores intellectual trends outside its own ambit, or, still worse, which adopts an abusive attitude to those ‘outside’ its group (especially if they are ‘western’) to that extent adopts an anti-Trinitarian mode of being. In so doing, it turns away from Christ, and so loses touch with the principle of its own theological life, thus forfeits its identity as theology, and certainly fails to be Orthodox theology. Just as truly personal, communal and kenotic prayer is for the whole world, and disregards all badges or labels, so Orthodox theology must explicitly concern itself with that which lies beyond the walls of the Orthodox academy. All Orthodox theology must have a concern for that which lies outside the Church in the world.

Nonetheless, whilst all theology must be concerned with what lies outside the Church, there can be no theology which is outside the Church. The theologian can only draw his or her life from the eschatological Christ, and theological speech is an eschatological ek-stasis and witness which attempts to stand outside all the pettiness and smallness of the world we live in at the moment and speak to that world from the vantage point of the Kingdom of God, a Kingdom which is tasted and shared in in the Church.

Alan Brown

Vincent Rossi on true theology

And what is the ideal of theology in the spiritual tradition of which St. Maximos is such a leading light? In that tradition, the patristic Orthodox tradition, the word ‘theology’, as Orthodox theologian Alexander Golitsin points out in another context, is used in at least five different levels of meaning—not five different meanings, but hierarchically, five different levels, of which only the fifth and lowest is rational, academic discourse on religious doctrine. When Dionysios or Maximos and others in the Philokalic ascetic tradition use the word ‘theology’, they mean first of all God in Trinity, then secondly, the unitive experience or gnosis of God in Trinity; then, thirdly, they mean by theology the worship of God, in particular the unity of the liturgy of the angels in heaven and the liturgy of the Church on earth; and fourthly, they use theology to refer to the Holy Scriptures. In other words, to ‘do’ theology properly in the Maximian, Palamite, Philokalic sense, is in some way to participate in Divinity. It is in that sense that Evagrios of Pontos, one of Maximos’ spiritual forefathers, can declare, in his work, On Prayer: ‘If you are a theologian, you will pray truly. And if you pray truly, you are a theologian’ (On Prayer 61). It is in this sense also, in the most Evagrian of his writings, the Centuries on Charity, that Maximos himself can say, using the same formula, which sounds almost impossibly severe: ‘He who truly loves God prays entirely without distraction, and he who prays entirely without distraction loves God truly. But he whose intellect is fixed on any worldly thing does not pray without distraction, and consequently he does not love God’ (Char. 2:1) True theology, even on the fifth level, must be free of distraction and grounded in prayer and love for God. And this is perhaps where I failed Alan Brown and Douglas Knight.

When I think of what another of St. Maximos’ eminent spiritual forefathers, St. Diadochos of Photiki (5th Cent.) had to say about theology, I am acutely aware of how far I am from this ideal. He writes, in his ‘On Spiritual Knowledge 7’:

‘Spiritual discourse fully satisfies our intellectual perception, because it comes from God through the energy of love. It is on account of this that the intellect (nous) continues undisturbed in its concentration on theology. It does not suffer then from the emptiness which produces a state of anxiety, since in its contemplation it is filled to the degree that the energy of love desires. So it is right always to wait, with a faith energized by love, for the illumination which will enable us to speak. For nothing is so destitute as a mind philosophizing about God when it is without Him.’

The Orthodox patristic theological tradition is, above all, an energetic theology, grounded in the energy of love. I cannot say with absolute conviction that my earlier post was the fruit of something that came from God through the energy of love. And for this I must ask the forgiveness of all who have read it. And when one thinks of what Diadochos says further on in ‘On Spiritual Knowledge’, one cannot help but be even further chastened, especially as this text embraces all four of the higher levels of theology mentioned above:

‘God is not prepared to grant the gift of theology to anyone who has not first prepared himself by giving away all his possessions for the glory of the Gospel; then in godly poverty he can proclaim the riches of the divine kingdom…All God’s gifts of grace are flawless and source of everything good; but the gift which inflames our heart and moves it to the love of His goodness more than any other is theology. It is the early offering of God’s grace and bestows on the soul the greatest gifts. First of all, it leads us gladly to disregard all love of this life, since in the place of perishable desires we possess inexpressible riches, the oracles of God. Then it embraces our intellect with the light of a transforming fire, and so makes it a partner of the angels in their liturgy. Therefore, when we have been made ready, we begin to long sincerely for this gift of contemplative vision, for it is full of beauty, frees us from every worldly care, and nourishes the intellect (nous) with divine truth in the radiance of inexpressible light. In brief, it is the gift which, through the help of the holy prophets, unites the deiform soul with God in unbreakable communion. So, among men as among angels, divine theology—like one who conducts the wedding feast—brings into harmony the voices of those who praise God’s majesty’ (On Spiritual Knowledge, 66-67)

And so, my friends, if my contribution to this theological conversation has not also contributed to bringing into harmony the voices of those who praise God’s majesty, then I ask your forgiveness for that lapse.

Vincent Rossi

You can read Vicent Rossi’s comment in its entirety here

The apprenticeship

Christianity is an apprenticeship. All professions – law, medicine, football – require apprenticeships, which involve their own craft skills and vocabulary. The logic of the practices peculiar to each of these cannot be seen immediately seen by the public. Nevertheless we do not demand that each specialism speaks only some neutral language in which all their judgments are completely accessible in the public domain. But it is part of our modern narrative that we should speak only neutral language and that we need no apprenticeship: we can know, everything, immediately, without effort.

Christians say that the Christian life is learned and lived like any other vocation or career, with the same element of adventure, which means that its path is not entirely clear from the outset. In fact they say this is how any life, not just the Christian life, is – everything requires training which means that nothing is immediate or effort-free. This means that the Christian hermeneutic is more sophisticated than the modern hermeneutic of immediacy, which wants us to believe that nothing has to be learned and that life doesn’t require any particular skills.

The package of Christian doctrine, which constitutes the Christian apprenticeship, has been taken apart in modern period and some of its components have been re-connected to re-create old Hellenic arrangement of two worlds, in which the world of the individual is prior to the public and political world. This arrangement does not concede that the individual gives or receives anything in his encounter with others, so we appear to have no real stake in other people. We are reluctant to concede that we are beings in time, or that we are really committed to the toil and change that comes with life with other people.

Here Christian theology, particularly in its patristic and Eastern Orthodox expression, can contribute decisively. It can show that Christians have an alternative way of regarding the world, a sophisticated ontology which factors in hope. They say that God is making the world more real, and that the ordinary environment of people and things is in process of becoming more vivid, more solid, engaged and interactive. This is what I have learned represented by Orthodox theology. Since catholicity alone says that we cannot leave out the insight of half the Church, though the Eastern tradition may not be better, its difference from our own helps us to see how we may better hold together what we have inherited from Augustine, and prevent it from being purloined by the champions of autonomy who want us to believe that life requires no skills and that we should therefore do without this, or any, apprenticeship.

Solly: Sons and persons

Solly is reading Chapter Three of The Eschatological Economy. Here is a snippet of his commentary:

‘It needs a reminder here that for Knight the idea that sacrifice means ‘making holy’ comes in part from the Latin roots of the English word ‘sacrifice’. It is necessary to see that this is also how the practice appears in scripture of course, supplemented by such insights of the practice that anthropologists can supply us with. Sacrifice is here presented not only as the work of the Israelite, but the work of God on the Israelite, of making him a son, of making him a person.

Knight returns to the modern sensitivities to the notion of vicarious and substitutionary action, as exemplified in Kant’s philosophy of religion, and how this encapsulates in nuce the economy of modernity’s understanding of individuality, and resistance to the idea of relationism. You cannot do something for me, in my place, A is A, and A is not not-A.

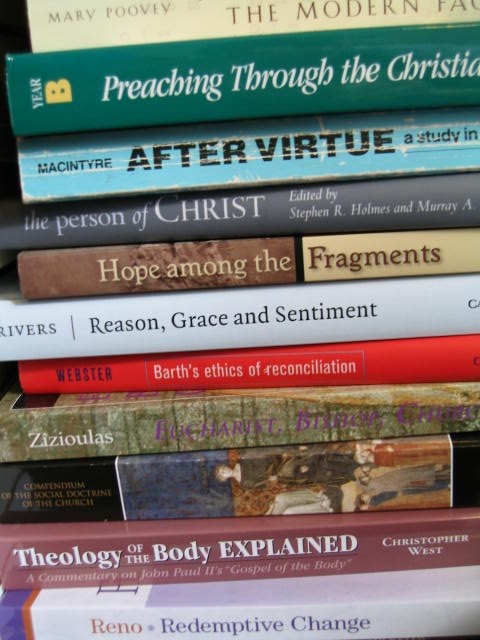

Given, Knight explains, modern theology’s appropriating this position, and the con-joined idea that we are already persons [though really only individuals] then that explains the difficulties found with the doctrine that we are God’s work, our becoming is basic, not our being. Existentialism expressed that garishness and angst of this position, of man no longer in relation with man, but isolated in spheres of completeness, yet knowing it was not really so. R R Reno Redemptive Change: Atonement and the Christian Cure of the Soul has also criticised modern thought for its inability to propound a doctrine of personal and moral change when it also holds to an idea of humanity that does not need change, each individual is complete in themself.’

Solly’s commentary is a model of clarity. I am beginning to wish he had intervened a bit earlier, when the book was still a-writing.

Here is more of Solly’s analysis of this Israel-and-Adam Christology.